RATIONALE. Strategic planning

Current international policies promote the development of a sustainable transport sector, asking to mainstream biodiversity through all transport infrastructure life cycle and preserve or restore ecological connectivity as a mean to achieve the United Nations´ Sustainable Development Goals (UN, 2015). The Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (CBD, 2022) includes it as part of its goal A ‘The integrity, connectivity and resilience of all ecosystems are maintained, enhanced, or restored, substantially increasing the area of natural ecosystems by 2050 (…)’.

At European scale recent strategies and policies are encouraging this international approach and including biodiversity as one of the central issues to achieve for sustainable development. Many of these policies are focused on climate change mitigation, and decarbonisation is the main topic when dealing with transport sector. This is the case of the ‘EU Green Deal’ (European Commission, 2019) and the ‘Fit for 55 package – The EU’s plan for a green transition’ (European Commission, 2021). Nevertheless, biodiversity and particularly the need for restoring nature and applying Nature-based Solutions (NbS) are also being included in the visions for 2030 and 2050 scenarios. For example, the EU Green Infrastructure Strategy (European Commission, 2013b) aims to preserve, restore and enhance green infrastructure to help stop the loss of biodiversity and enable ecosystems to deliver their services to people. Also, the EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 (European Commission, 2020) promotes investments in green and blue infrastructure, as well as the systematic integration of healthy ecosystems, green infrastructure and NbS into urban planning. Improving the development of green infrastructure can be facilitated by its further integration into spatial planning tools, Strategic Environment Assessment and Environmental Impact Assessment processes.

These spatial planning tools also need to consider the cumulative impacts of new development projects. When these new projects are new transport infrastructure a common solution applied is ‘bundling’ them and creating transport corridors, which in some cases may not be the best solution (Reck et al., 2023). A ‘case by case’ approach is needed, as it is recommended in ‘A Global Strategy for Ecologically Sustainable Transport and other Linear Infrastructure’ (Georgiadis et al., 2020), published by IENE, aiming to achieve sustainable transport infrastructure and whose principles are also included in the present chapter. Another step to achieve a sustainable transport infrastructure network is to restore ecological connectivity in those infrastructure built decades ago without current knowledge and objectives. To do so, several countries have implemented, or are in the process of implementing, National Defragmentation Programmes following the example of the pioneer Dutch National Defragmentation Program (Sijtsma et al., 2020). In this sense, the European Defragmentation Map developed in the framework of the HORIZON 2020 BISON project highlights the conflict points where these defragmentation measures should be implemented.

Phase characteristics

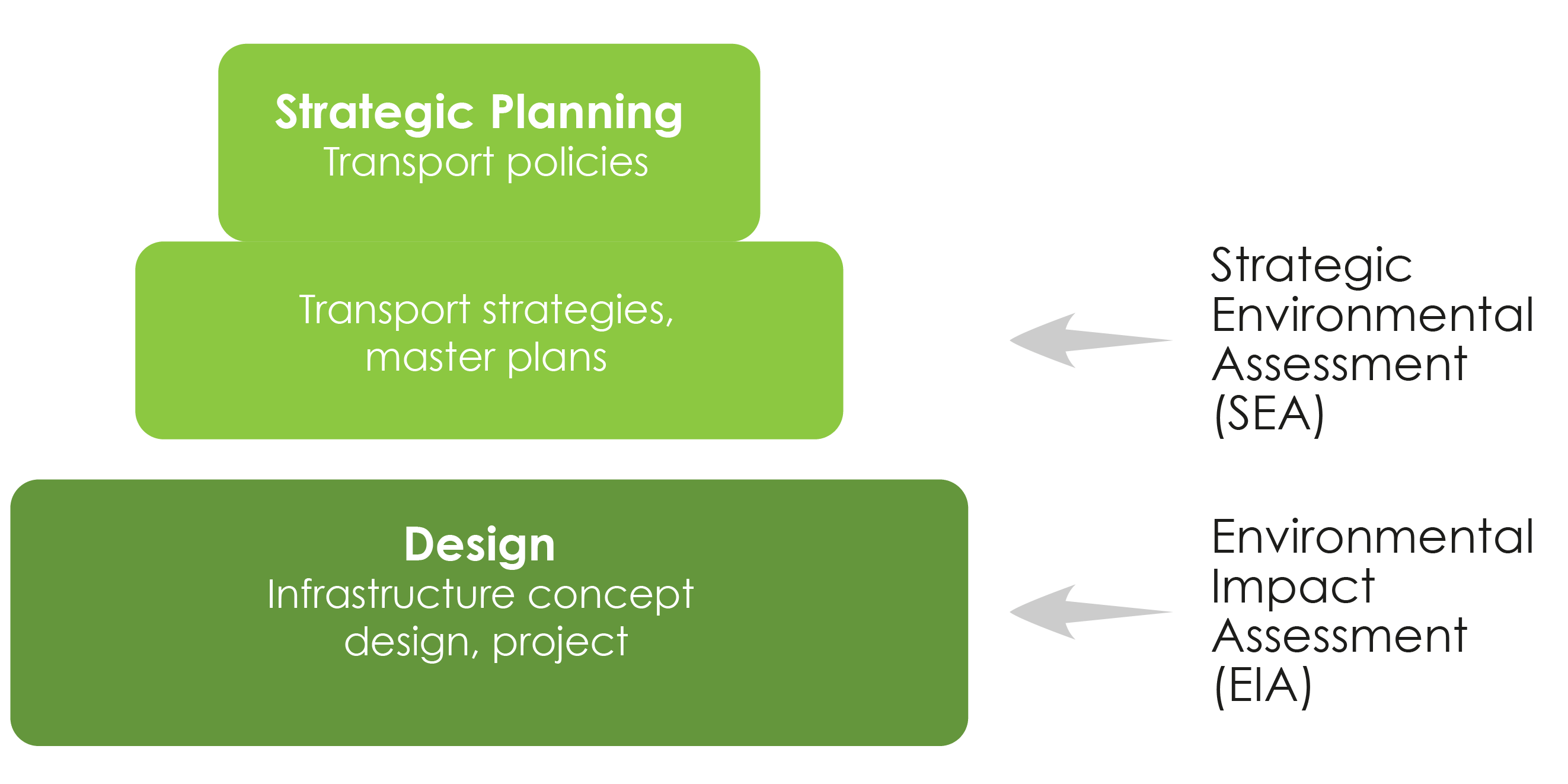

Strategic planning should build from existing and relevant policies to ensure the strategies, plans and programmes that follow are aligned with, for example, transport and sustainability policies (Figure 2.2.1). Implementing policy through plans, strategies, programmes, and projects (detailed design of the infrastructure), and then assesses these through impact assessment is fundamental to ensure coherence in the decision-making process. With this hierarchy in mind, the strategic planning phase starts with a number of steps beginning with definition of general goals and vision for transport corridors, identifying the needs for transport infrastructure in a region or country, and providing specifications about priorities, location and planned schedule. Two subphases are included: i) Transport policy and, ii) Transport Strategy and delimitation of areas and corridors.

Transport policy

The transport policy sets the principles for future transport development in a given area. It is usually implemented through a document developed at national or regional level, depending on the administrative structure of the country.

Towards developing National Transport Policies with sustainability in mind, an approach of two basic steps must be followed:

- Consider national commitments made by countries through international environmental agreements such as the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) of the Convention on Biological Diversity or the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

- Integrate these commitments, associated frameworks and concepts into national transport policies following the ‘acting locally thinking globally’ principle and ensure this integration is carried out through meaningful stakeholder consultation.

International environmental agreements

Transport networks facilitate the connection of people and provide access to key services, while they also catalyse and promote economic activity beyond national borders. However, according to the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), the transport sector is closely connected, directly or indirectly, to the five main direct drivers of biodiversity loss: i) Land-use and sea-use change; ii) Direct exploitation of organisms; iii) Climate change; iv) Pollution and v) Invasive Alien Species (see Chapter 1 – Ecological effects of infrastructure for more details).

The loss of biodiversity, its impact on the delivery of ecosystem services, as its effects on society and the economy, has become one of the main environmental challenges together with the need for action on climate change which hinder the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Similarly, the United Nations (UN) declared the running decade as the ‘Decade of restoration’ to reverse existing negative impacts on biodiversity and halt, or even reverse, its loss. In 2018 the Parties of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) agreed mainstreaming of biodiversity in infrastructure and other sectors in Decision 14/3 of the 14th Conference of the Parties (COP). The same year the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) published a special policy report defining entry points for mainstreaming biodiversity in all development sectors at a national level. In 2022, the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework was agreed at the 15th COP of the CBD which includes goals and targets to be advanced globally by the 193 signatory countries aiming to achieve the integrity, ecological connectivity, and resilience of all ecosystems.

EU transport policy

The European transport system is one of the key elements that allows the internal EU market to function, ensuring free movement of persons and goods among the member states. EU transport policies are the basis for the development of transport infrastructure, but they are not subject to Strategic Environmental Assessment. The consequence is that evaluation of the impact of such transport policies on biodiversity is missing.

The White Paper on Transport and Transport 2050, both adopted by the European Commission in March 2011, form the basic documents for European transport policy. These documents outlined the strategic vision that should be gradually fulfilled in the sector of transportation over the coming years. In 2023, the ‘Fit for 55 packages’, the EUs plan for a green transition, were approved which updated EU legislation regarding climate change. It includes:

- Legally binding the goal of reducing EU emissions by 55% by 2030, aiming to be climate-neutral by 2050.

- Introducing progressive EU-wide emissions reduction targets for vehicles for 2030 and beyond

- Aiming to reduce the aviation sector’s environmental footprint and enabling it to help the EU achieve its climate targets.

- Proposing the use of renewable and low-carbon fuels in maritime transport to reduce the greenhouse gas intensity of the energy used on-board by ships by up to 75% by 2050.

Another key element of the EU transport policy is the Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T). This policy addresses the development of a European wide network of all transport mode infrastructures: roads, railways, inland waterways, ports and airports. It aims to build networks in transport, telecommunications and energy supply, including oil and gas pipelines. The main goals are:

- To contribute to social and economic cohesion between richer and less developed regions of the EU. More reliable communication and easier and cheaper transportation among these regions should accelerate economic development of underdeveloped regions and decrease differences in gross domestic product (GDP) per capita.

- To set priorities in developing infrastructure, which should positively influence particularly more remote and less developed EU regions.

- To strengthen competitiveness of the EU, to create new markets and new employment opportunities.

- To create necessary connections with associated Central and East European countries and countries of the Mediterranean.

In 2009, the Green Paper ‘TEN-T: A policy review – Towards a better integrated trans-European transport network at the service of the common transport policy’ was published. This document discusses possibilities for connecting the current trans-European network projects to the issue of fighting climate change and strengthening ties with EU neighbouring countries. The current TEN-T policy is based on Regulation (EU) No 1315/2013 of the European Parliament and of the European Council. In addition to the construction of new physical infrastructure, the TEN-T policy supports innovation, the application new technologies and digital solutions for all modes of transport. The objectives are the improved use of infrastructure, reduce environmental impact of transport, enhance energy efficiency and increase safety. TEN-T comprises two network layers:

- The Core Network includes the most important connections, linking the most important nodes, and is to be completed by 2030.

- The Comprehensive Network covers all European regions and is to be completed by 2050.

In April 2019, the Commission launched a review of the TEN-T. The TEN-T policy supports and enhance connectivity and accessibility for all regions of the Union. Through several revisions, the policy has coped with a growing transport demand, geo-political developments (several EU enlargements) and evolving transport policy challenges (e.g. liberalisation, standardisation, technological innovation).

European Green Deal and Strategies for Green Infrastructure and Biodiversity

The Green Deal is the EU’s main new strategy to transition the EU economy to a sustainable economic model. Presented in December 2019, the overarching objective of the EU Green Deal is for the EU to become the first climate neutral continent by 2050, resulting in a cleaner environment, more affordable energy, smarter transport, new jobs and an overall better quality of life. The Sustainable Mobility policy area comprises initiatives to reduce transport emissions, which account for 25% of the EU’s greenhouse gas emissions. The adopted Strategy for Sustainable and Smart Mobility lays the foundation for action to transform the EU transport sector, with the aim of a 90% cut in emissions by 2050, delivered by a smart, competitive, safe, accessible and affordable transport system. The Green Deal also aims to tackle biodiversity loss and to restore nature, including the EU biodiversity Strategy for 2030.

The EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 is a comprehensive, ambitious, and long-term plan to protect nature and reverse the degradation of ecosystems. The strategy aims to put Europe’s biodiversity on a path to recovery by 2030, and contains specific actions and commitments to be considered in transport infrastructure development such as the reduction of pesticides and fertilisers, the AIS control or the application of Nature-based Solutions. However, this document does not address the crucial role of infrastructure development on habitat loss and fragmentation and does not establish any objectives which relate to avoidance and reduction of impacts on biodiversity caused by transport infrastructure.

The EU Strategy for Green Infrastructure aims to ensure the protection and restoration of a strategically planned network of natural and semi-natural areas with other environmental features designed and managed to deliver a wide range of ecosystem services. Considering the Green Deal and the EU’s Biodiversity strategy for 2030, particular attention should be paid to the way in which these instruments can promote green infrastructure. It requires a wider look at all rural and urban green areas, and also beyond national borders to connect between to facilitate movement of species. Enhancing ecological connectivity is not the only positive outcome of green infrastructure. In addition, it could contribute to improving public health and could be an efficient way of reducing current (or future) weather and climate-related natural hazards.

National and regional transport policies

National and regional transport policies set priorities for future transport development in specific countries. They are based on the socio-economic needs of society and take into consideration transnational concepts such as Transport Policy of the EU, including compliance with TEN-T statements. The national transport policy determines the transport modes to be used and defines priorities for transport connections, and are usually approved by the governments of each country.

Transport strategy and delimitation of areas and corridors

Strategic transport master plans are based in transnational and national transport policies. They provide detailed action plans identifying actions to be undertaken and its spatial distribution as well as establishing priorities. These plans are prepared for a specific time period. Similar to policies, strategic plans are also prepared at the European, national and regional level. General environmental and biodiversity protection principles should be part of every strategic transport master plan. These plans must also specify individual measures and set down a framework time schedule for their implementation.

Once a transport plan is agreed, the delimitation of transport corridors (or sites where infrastructure are going to be developed) takes place.This includes defining the broader area where a future transport infrastructure project should be implemented. The corridor is usually delimited informed by feasibility studies. Major conflicts with areas of importance for biodiversity and important migration corridors must be identified at this stage. In most countries, a defined transport corridor is incorporated into spatial plans to preserve it from urban development. In the following phase, different alternatives for placement are then checked and assessed within this area.

Key issues to be addressed

Transport policy

A ‘Global Strategy for Ecologically Sustainable Transport and other Linear Infrastructure’ to promote mainstreaming biodiversity and ecological connectivity in transport policy was developed by IENE supported by an international coalition formed by organisations leading international conferences on transport and ecology and conservation organisations (i.e., IENE, ICOET, ANET, ACLIE, WWF and IUCN). This Global Strategy provides the basic elements required to be used and integrated in the development of transport policies and strategies in harmonization with biodiversity conservation. The 12 basic principles for sustainable transport linear infrastructure are listed in Table 2.2.

Table 2.2 – The basic principles of Sustainable Transport Linear Infrastructure (TLI) need to adopted according to the ‘Global Strategy for Ecologically Sustainable Transport and other Linear’.

| Principle | Description | |

| 1 | Strong policy and legal framework | Safeguarding landscape connectivity as a primary concern for any project scale, establishment and strengthening of a policy and legal framework of regulatory requirements for sustainable TLI development is necessary. |

| 2 | Strategic planning | Any major TLI should be based on an overall strategic plan, and designed and developed to guarantee ecological fluxes and well-connected wildlife populations before any implementation and funding decision is made. The Mitigation Hierarchy of ‘Avoidance – Mitigation – Compensation’ should also be implemented. |

| 3 | Ecosystem approach | TLI projects should combine habitat quality with healthy ecosystem functioning based on the ‘Precautionary Principle’. The value of Natural Capital and ecosystems services should be included along with projects that acknowledge cultural diversity, as an integral component of ecosystems. |

| 4 | ‘Any case is a unique case’ | Each TLI project is site- and species-specific and is therefore unique. Mitigation should be based on scientific and best available local knowledge without ‘copy and paste’ from other projects. |

| 5 | Multi-disciplinary and cross-sector cooperation | To ensure integration and coordination, the establishment of multi-level governance and stakeholder engagement, with multi-disciplinary cooperation amongst different professionals (such as engineers, policy makers, economists, ecologists and environmentalists) as well as cross-ministerial agencies (such as nature conservation, transportation, finances) should be applied. |

| 6 | Stakeholder involvement and public participation | Involvement of civil society and all the relevant stakeholders in the development of TLI projects. |

| 7 | Responsible ‘polluter pays’ principle | Implementation of the ‘polluter pays’ principle where the integration of environmental consideration is responsible for TLI investments, after clarifying the ethical and transparency concerns; this should include concrete mitigation measures from the onset of the TLI planning phase, until the tendering and contracting, and finally to the building and operating phases. |

| 8 | Long-term effective maintenance | Inclusion of TLI maintaining mitigation measures in the budget for all the duration of the operation phase. |

| 9 | Resilience to climate change | TLI should be planned or adapted with consideration for their resilience to natural disasters and risks, associated with extreme weather events and climate change. This is especially the case for TLI, where responses to stronger and intense precipitation with larger bridges and culverts servicing both hydraulic and ecological connectivity purposes is a critical requirement. |

| 10 | Adaptable infrastructure habitats | Habitats related to TLI should be planned and managed in a manner that fulfils their potential as positive biodiversity refuges and ecological corridors. |

| 11 | Environmental supervision | Inclusion of environmental supervision that monitors the effectiveness of TLI features and the habitat and wildlife populations in all phases of programmes, plans and projects; this is within the Strategic Environmental Assessment, Environmental Impact Assessment to the design of full operation and maintenance. |

| 12 | Culture of learning | Establishment of a culture of learning to develop and support continuous evaluation and exchange of knowledge and experience between the interested, relevant and authorised organisations and state services. |

The engagement of stakeholders noted in principle 6 is considered as crucial factor. Understanding their role in infrastructure planning is critical to screen, assess and prioritise actions.

Towards shaping the final stakeholders’ roadmap four categories can be used to understand the role they can play:

- Informative role: Stakeholders who have little interest but may be affected by the strategy. It is important to assist them in understanding the key problems and promoting potential solutions;

- Consultancy role: Stakeholders with high interest, low influence but they are supportive;

- Involvement role: Stakeholders that work partially or directly with interested third parties. It is important to ensure their concerns and aspirations are understood, considered and, where appropriate, incorporated into decision making; and,

- Fundamental collaborator roles: Stakeholders who work in partnership with relevant aspects and phases of a transport linear infrastructure development process from the decision-making and planning stages through to the implementation, operation, and maintenance phases of a project.

Further elements of the Global Strategy can be used to inform development of sustainable transport policies such as the definition of sustainable transport and elements of the proposed Action Plan which covers four levels: (i) Policy and Strategy and SEA; (ii) Planning and EIA; (iii) Implementation and management level and (iv) Education, awareness, consultation and communication.

To mainstream biodiversity in national and regional policies is evaluated as fundamental, primary to recognise the impact of transport network to the landscape and habitat fragmentation, and secondly to adopt a defragmentation approach. Such an approach of transport development must establish two strategies depending on the existence status of the infrastructure in combination with the enforcement of the Mitigation Hierarchy (see Chapter 3 – The mitigation hierarchy). In new transport infrastructure planned to be constructed in pristine areas a strategy of avoiding fragmentation must be adopted to preserve roadless areas aand in general, areas free from any transport infrastructure development.

In the cases of upgrading existing infrastructure a defragmentation strategy must be adopted in order to take the appropriate measures to re-establish the ecological connectivity. Several European countries are developing National Defragmentation Plans following the example of the pioneer Dutch National Defragmentation Programme which was completed in 2018 and which benefits have been evaluated.

Transport strategy and delimitation of areas and corridors

During the strategic planning phase, it is essential to assess transport strategies and concepts for different modes of transport with policies and strategies aimed to conserve biodiversity. Compliance with other strategies and policies is a basic condition to avoid conflicting decisions. For example, project proponents must evaluate the impact of the proposed development on the Natura 2000 network, and Emerald Network -in European countries which are not part of the EU- ensuring its integrity, as well as effects on protected areas and ecological connectivity. Other planning tools aimed at maintaining or restoring the quality of specific environments such as rivers, sea, coastal and other aquatic ecosystems should also be considered. Table 2.3 provides some details about the key issues to be addressed depending on the types of infrastructure.

Another key issue to be addressed is the cumulative effect of transport infrastructure (see Chapter 3 – The mitigation hierarchy), especially in cases of pair transport systems (e.g. a railway and a road running together in a transport corridor), together with other types of infrastructure, urbanisation or other human activities in the area. For transnational transport infrastructure, agreements must be reached to comply with the environmental requirements between countries. Available maps of ecological networks, and corridors including supra-regional significant animal migration corridors should also be used to assess the effects of the proposed development on habitat fragmentation. The analysis of data at a strategic scale also helps to identify conflict points, propose appropriate alternatives, and avoid many conflicts and potential impacts in the next stages of infrastructure planning.

Table 2.3 – Key issues to be addressed during the strategic planning phase in different types of transport infrastructure.

| Type of transport infrastructure | Key issues to be addressed during strategic planning phase to reduce the impact on biodiversity |

| All | Avoiding the destruction and fragmentation of valuable species and habitats, the intersection of ecological corridors and any conflict with ecological networks of national and supranational significance. Identifying conflict points, and assessing of most suitable alternatives, paying special attention to the cumulative effects on biodiversity from transport infrastructure. |

| Roads and railways | Avoiding areas where important mortality risk by traffic are expected and conflict with important ecological corridors and areas important for wildlife |

| Powerlines | Avoiding conflict with important migration routes and areas important for birds, especially species threatened by electrocution (birds of prey, storks etc.) and collisions (water birds, etc.), checking the possibility of integration of the powerline protection zone into the ecological network. |

| Pipelines | Avoiding destruction of natural habitats, checking the possibility of integration of the pipeline protection zone into the ecological network |

| Waterways | Avoiding fragmentation and destruction of both river and terrestrial habitats, fragmentation of watercourses, obstruction to fish migration or other wildlife species movements (otter, beaver, crayfish etc.) and colonization by invasive species. |

| Ports | Avoiding occupation of coastal and wetland habitats, preserving the functionality of habitats, anticipating the risk of development of the neighbouring countryside. Assessing cumulative impacts on biodiversity from activities linked to the port’s development (offshore energies, dredging, extractions etc.) or other transport modes (road, railways, connection with airports) and the risk of spreading invasive alien species. |

| Airports | Avoiding the occupation and destruction of valuable natural habitats, avoiding any conflict with ecological networks of national and supranational significance, assessing the risk of development of the neighbouring countryside and disturbances to surrounding habitats, identification of more suitable alternatives of airport locations, paying special attention to the cumulative effect on biodiversity, assessing and confront the risk of spreading invasive alien species. |

Processes and tools

One of the main barriers to mainstream biodiversity conservation and green infrastructure on transport policies is what is known as ‘the implementation gap’. This means that excellent policy documents may achieve very few targets in practice due to a deficient implementation. The latter is often associated with lack of political will and weak regulation enforcement. Concrete process and tools are available to manage this.

Processes for policy and strategies development can include the following:

- Implementation of international environmental agreements through concrete National Action Plans transposed to the national legal, administrative and institutional systems.

- Mainstream EU Strategies for biodiversity and green infrastructure in National Transport Policies enforcing defragmentation practices.

- Build synergies between the policy makers, scientists, and practitioners before making decisions based on updated knowledge and innovation.

- Mainstreaming of biodiversity in national budgeting for transport and all other sectors.

- Ensure that in the processes of procurement and assignment, the companies, state or private, have the will and capacity to implement appropriate biodiversity mitigation measures during construction and operation.

- Establish a permanent follow up process based on environmental monitoring and specialized indicators.

Tools for policy and strategies development can include the following:

- National and regional databases for biodiversity status, species distribution, ecological corridors, and green infrastructure.

- Legal instruments such as laws (creating new or amending of existing), ministerial degrees, and regulations among others.

- Technical tools such as guidelines, standards, and protocols for evidence-based, innovative and nature-based solutions.

- Tools and mechanisms for capacity building of existing staff and experts to promote a culture of learning among scientists and practitioners.

Transport strategy and delimitation of areas and corridors

The assessment of the effects of certain plans, strategies, and programmes on the environment are subject to the process of Strategic environmental assessment (SEA) as a result of Directive 2001/42/EC. The objective of this Directive is to provide for a high level of protection of the environment and to contribute to the integration of environmental considerations into the preparation and adoption of plans and programmes with a view to promoting sustainable development. The SEA Directive is taken as a baseline to ensure the environmental assessment procedures at the planning and programming level including relevant environmental information into decision-making. Transport development, specifically, strategic transport plans and delimiting transport corridors, are all subject to the SEA procedure.

According to the SEA Directive, the process follows these steps:

- Notification

- Screening – determining whether or not SEA is required

- Scoping – describing what the policy, plan or programme’s aim is, if there are any significant strategic issues, who the stakeholders are and what the current state of the environment is. The range and depth of assessment is determined based on this analysis

- Environmental reporting with the environmental assessment before starting to work out the evaluation

- Consultation:

- Opinion of an expert group

- Public announcement and consultation

- Opinion of competent authorities and relevant stakeholders

- Transboundary consultation in case of cross-border plan or programme

- Taking the opinions and other comments into account

- Decision

- Follow up and adaptive management

- Monitoring in order to identify at an early-stage unforeseen adverse effects and to be able to undertake appropriate remedial action.

Appropriate involvement of the public is an important part of the process across these phases, especially in early stages of the process. It includes developing relevant documents collaboratively, making related information and documents public, seeking comments, and holding public hearings.

For transport strategic plans and programmes, the SEA should always include an evaluation of habitat fragmentation, before too much political and financial efforts have been directed towards a specific alternative. Specifically in Europe, general principles for ensuring the connectivity of the Natura 2000 network and the permeability of the main migration corridors must be addressed within the SEA process.

A map containing the outlines of Natura 2000 areas, Emerald Network, national protected areas and delimitation of ecological networks, including significant animal migration corridors, should be part of the assessment. It’s crucial to delimit transport corridors considering the avoidance of impacts to ecological corridors and natural areas which require to produce common maps of Trans-European Nature Network (TEN-N) and Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T) to define the critical conflict points. The European ’Defragmentation Map’ produced in the framework of the BISON project may contribute to identify existing conflict and to prevent development of new infrastructure. Detailed technical solutions are not proposed within the SEA, however, principles to avoid, reduce or compensate (ARC framework, see Chapter 3 – The mitigation hierarchy) for negative impacts of constructing transport infrastructure on fauna in conjunction with rough estimation of cost associated for minimising the impact must be described in sufficient detail. The essential task is to identify potential problems and critical issues and to propose general solution procedures.